At the moment the Hashed index types can be used only in both leaf and non-leaf positions. The FIFO index types must always be in the leaf position, they don't allow the further nesting.

Now is the moment to look deeper into what is going on inside a table. Note that I've been very carefully talking about "index types" and not "indexes". In this post the difference matters. The index types are in the table type, the indexes are in the table. One index type may generate multiple indexes.

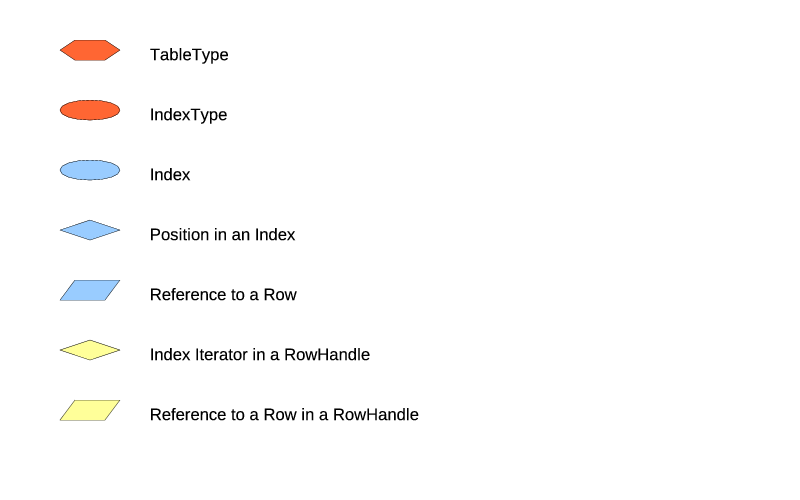

This will become clearer after you see the illustrations. I really hate doing the drawings, but here they are really necessary for the understanding, and way too complex for the ASCII-art. But first, the legend on Fig. 1.

|

| Fig. 1. Drawings legend. |

The nodes belonging to the table type are shown in red, the nodes belonging in the table are shown in blue, and the contents of the RowHandle is shown separately in yellow. The lines on the drawings represent not exactly pointers as such but more of the logical connections that may be more complicated than the simple pointers.

The lines in the RowHandle don't mean anything at all, they just show that the parts go together. In reality a RowHandle is a chunk of memory, with various elements placed in that memory. As far as indexes are concerned, the RowHandle contains an iterator for every index where it belongs. This lets it know its position in the table, to iterate along every index, and, most importantly, to be removed quickly from every index. A RowHandle belongs to one index of each index type, and contains the matching number of iterators in it.

The table type is shown as a normal flat tree. But the table itself is more complex and becomes 3-dimensional. Its "view from above" matches the table type's tree but the data grows "up" in the third dimension.

Let's start with the simplest case: a table type with only one index type. Whether the index type is hash or FIFO, doesn't matter here.

TableType +-IndexType "A"

Fig. 2 shows the table structure.

|

| Fig. 2. One index type. |

The table here always contains exactly one index, matching the one defined index type, and the root index. The root index is very dumb, its only purpose is to tie together the multiple top-level indexes into a tree.

The only index of type A provides an ordering of the records, and this ordering is used for the iteration on the table.

For the next example let's look at the straight nesting at fig. 3.

TableType +-IndexType "A" +-IndexType "B"

|

| Fig. 3. Straight nesting. |

There is still only one index of type A. And this is always the case with the top-level indexes, there is only one of them. This index divides the rows into 3 groups. Just like the rows in a leaf index, the groups in a non-leaf index are ordered in some way.

Each group then has its own second-level index of type B. Which then defines an order for the rows in it. To reiterate: the index of type A splits the rows by groups, then the group's index of type B defines the order of the rows in the group.

So what happens when we iterate through the table and ask for the next row handle? The current row handle contains the iterators in the indexes of types A and B. The easy thing is to advance the iterator of type B. Yeah, but in which index? The figure shows 3 indexes of type B, let's call them B1, B2 and B3. The iterator of type B in the row handle tells the relative position in the index, but it doesn't tell, which index it is. We need to step back and look at the index type A. It's the top-level index type, so there is always only one index for it. Then we take the iterator of type A and find this row's group in the index A. The group contains the index of type B, say B1. We can then take this index B1, take the iterator of type B from the row handle, and advance this iterator in this index. If the advance succeeded, then great, we've got the next row handle. But if the current row was the last row in B1, we need to step back to the index A again, advance the current row handle's iterator of type A there, find its index B2, and pick the first row handle of B2.

This process is what happens when we say $table->nextIdx($itB, $rh) or equivalently $rh->nextIdx($itB). The iteration goes by the leaf index type B, however it relies on all the index types in the path from the table type to B. If we do $rh->next(), the result is the same because the first leaf index type is used as the default index type for the iteration.

If we do $rh->next($itA), the semantics is still the same: return the next row handle (not the next group). There is no way to get to the row handle without going all the way through a leaf index. So when a non-leaf index type is used for the iteration, it gets implicitly extended to its first nested leaf index type.

What would happen if a new row gets inserted, and the index type A determines that it does not belong to any of the existing groups? A new group will be created and inserted in the appropriate position in A's order. This group will have a new index of type B created, and the new row inserted in that index.

What would happen if both rows in B1 are removed? B1 will become empty and will be collapsed. The index A will delete the B1's group and B1 itself, and will remain with only two groups. The effect propagates upwards: if all the rows are removed, the last index of type B will collapse, then the index A will become empty and also collapse and be deleted. The only thing left will be the root index that stays in the existence no matter what.

When a table is first created, it has only the root index. The rest of the indexes pop into the existence as the rows get inserted. If you wonder, yes, this does apply to a table type with only one index type as well. Just this point has not been brought up until now.

Among all this froth of creation and collapse the iterators stay stable. Once a row is inserted, the indexes leading to it are not going anywhere (at least until that row gets removed). But since other rows and groups may be inserted around it, the notion of what row is next, will change over time.

No comments:

Post a Comment