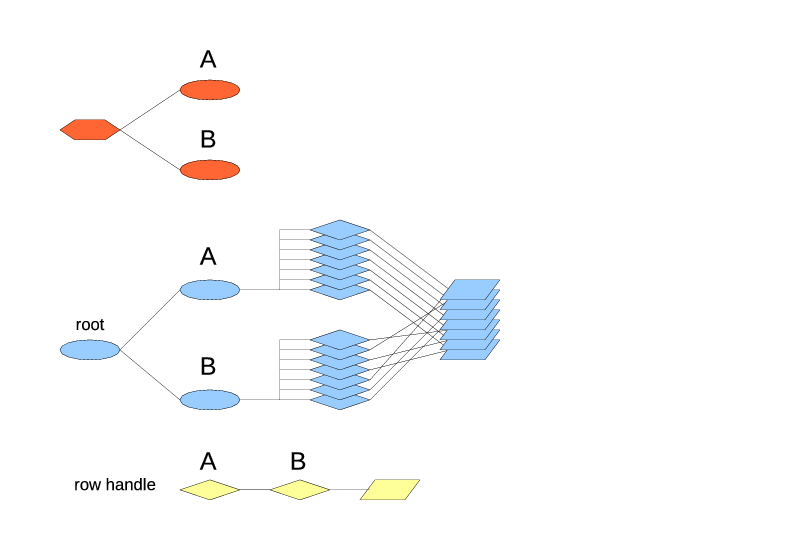

TableType +-IndexType A +-IndexType B

The resulting internal arrangement is shown on Fig. 8.

|

| Fig. 8 Two top-level index types. |

Each index type produces exactly one index under the root (since the top-level index types always produce one index). Both indexes contain the same number of rows, and exactly the same rows. When a row is added to the table, it's added to all the leaf index types (one actual index of each type). When a row is deleted from the table, it's deleted from all the leaf index types. So the total is always the same. However the order of rows in the indexes may differ. The drawing shows the row references stacked in the same order as the index A because the index A is of the first leaf index type, and as such is the default one for the iteration.

The row handle contains the iterators for both paths, A and B. It's pretty normal to find a row through one index type and then iterate from there using the other index type.

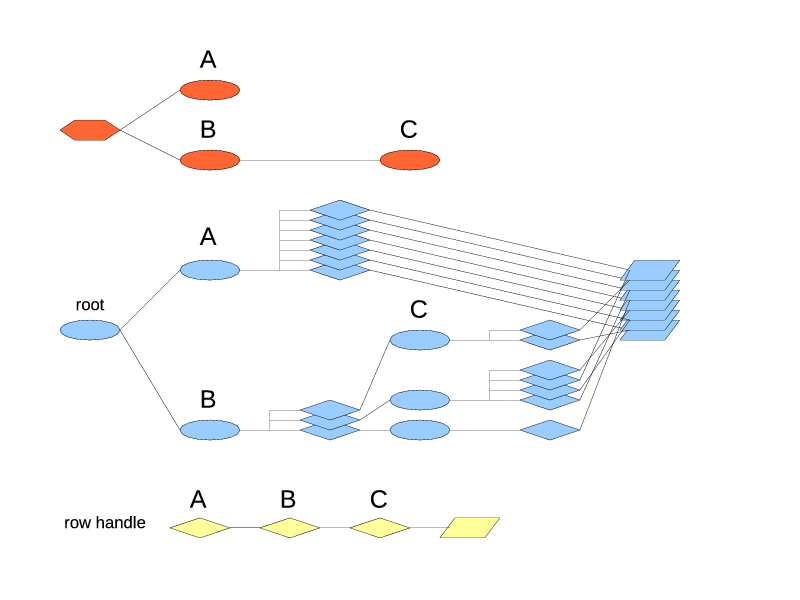

The next example on Fig. 9 has a "primary" index with a unique key and a "secondary" index that groups the records:

TableType +-IndexType A +-IndexType B +-IndexType C

|

| Fig. 9. A "primary" and "secondary" index type. |

The index type A still produces one index and references all the rows directly. The index of type B produces the groups, with each group getting an index of type C. The total set of rows referrable through A and through B is still the same but through B they are split into multiple groups.

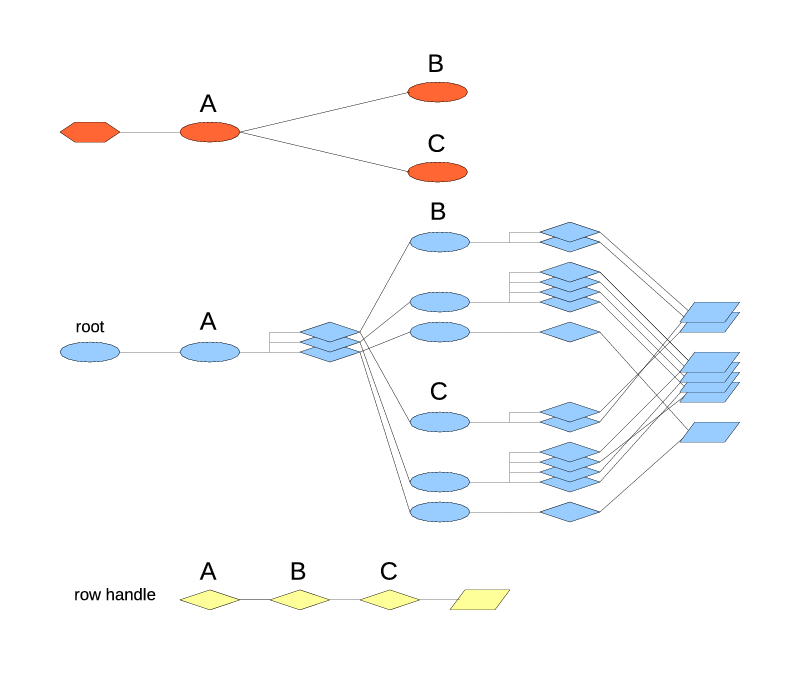

And Fig. 10 shows two leaf index types nested under one non-leaf.

TableType +-IndexType A +-IndexType B +-IndexType C

|

| Fig. 10. Two index types nested under one. |

As usual, there is only one index of type A, and it splits the rows into groups. The new item in this picture is that each group has two indexes in it: one of type B and one of type C. Both indexes in the group contain the same rows. They don't decide, which rows they get. The index A decides, which rows go into which group. Then if the group 1 contains two rows, indexes B1 and C1, would both contain two rows each, the exact same set. The stack of row references has been visually split by groups to make this point more clear.

This happens to be a pretty useful arrangement: for example, B might be a hash index type, or in the future, a sorted index type, allowing to find the records by the key (and for the sorted index, to iterate in the order of keys), while C might be a FIFO index, keeping the insertion order, and maybe keeping the window size limited.

That's pretty much it for the basic index topologies. Some much more complex index trees can be created, but they would be the combinations of the examples shown. Also, don't forget that every extra index type adds overhead in both memory and CPU time, so avoid adding indexes that are not needed.

One more fine point has to do with the replacement policies. Consider that we have a table that contains the rows with the single field:

id int32

And the table type has two indexes:

TableType +-IndexType "A" HashIndex key=(id) +-IndexType "B" FifoIndex limit=3

Then we send there the rowops:

INSERT id=1 INSERT id=2 INSERT id=3 INSERT id=2

The second insert of id=2 triggers the replacement policy in both index types. In the index A it is a duplicate key and will cause the removal of the previous row with id=2. In the index B it overflows the limit and pushes out the oldest row, the one with id=1. If both records get deleted, the resulting table contents will be 2 rows (shown in FIFO order):

id=3 id=2

Which is probably not the best outcome. It might be tolerable with a FIFO index and a hashed index but gets even more annoying if there are two FIFO index types in the table: one top-level limiting the total number of rows, another one nested under a hashed index, limiting the number of rows per group, and they start conflicting this way with each other.

So the FIFO index is actually smart enough to avoid such problems: it looks at what the preceding indexes have decided to remove, checks if any of these rows belong to its group, and adjusts its calculation accordingly. In this example the index B will find out that the row with id=2 is already displaced by the index A. That leaves only 2 rows in the index B, so adding a new one will need no displacement. The resulting table contents will be

id=1 id=3 id=2

However here the order of index types is important. If the table were to be defined as

TableType +-IndexType "B" FifoIndex limit=3 +-IndexType "A" HashIndex key=(id)

then the replacement policy of the index type B would run first, find that nothing has been displaced yet, and displace the row id=1. After that the replacement policy of the index type A will run, and being a hashed index, it doesn't have a choice, it has to replace the row id=2. And both rows end up displaced.

If the situations with automatic replacement of rows by the keyed indexes may arise, always make sure to put the keyed leaf index types before the FIFO leaf index types. However if you always diligently send a DELETE before the INSERT of the new version of the recond, then this problem won't occur and the order of index types will not matter.

No comments:

Post a Comment