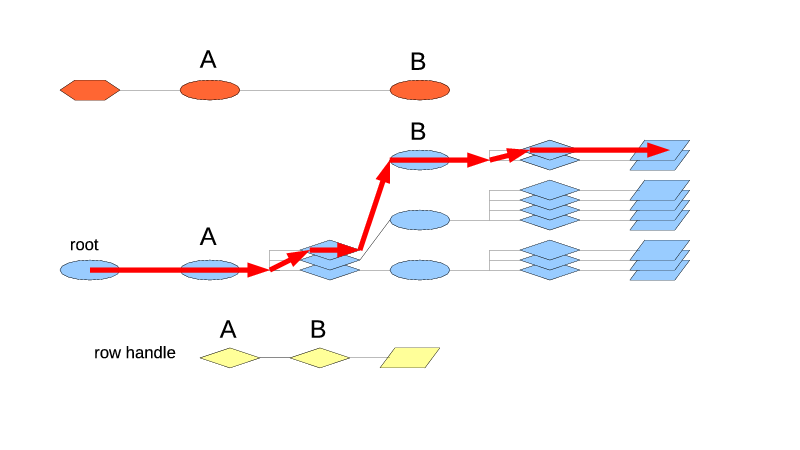

The iteration through the whole table starts with begin() or beginIdx(), the first being a form of the second that always uses the first leaf index type. BeginIdx() is fairly straightforward: it just follows the path from the root to the leaf, picking the first position in each index along the way, until it hits the RowHandle, as is shown in Fig. 4. That found RowHandle becomes its result. If the table is empty, it returns the NULL row handle.

If you specify a non-leaf index type as an argument of beginIdx(), the look-up can not just stop there because the non-leaf indexes are not directly connected to the row handles. It has to go through the whole chain to a leaf index. So, for a non-leaf index type argument the look-up is silently extended to its first leaf index type.

|

| Fig. 4. Begin(), beginIdx($itA) and beginIdx($itB) work the same for this table. |

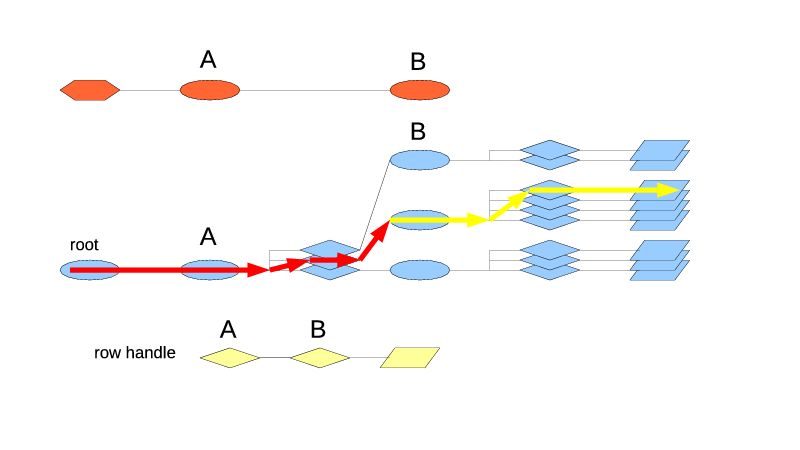

The next pair is find() and findIdx(). As usual, find() is the same thing as findIdx() on the table's first leaf index type. It also follows the path from the root to the target index type. On each step it tries to find a matching position in the current index. If the position could not be found, the search fails and a NULL row handle is returned. If found, it is used to progress to the next index.

As has been mentioned before, the search always works internally on a RowHandle argument. If a plain Row is used as an argument, a new temporary RowHandle will be created for it, searched, and then freed after the search. This works well for two reasons. First, the indexes already have the functions for comparing two row handles to build their ordering. The same functions are reused for the search. Second, the row handles contain not only the index iterators but also the cached information from the rows, to make the comparisons faster. The exact kind of cached information varies by the index type. The FIFO indexes use none. The hashed indexes calculate a hash of the key field values, that will be used as a quick differentiator for the search. This information gets created when the row handle gets created. Whether the row handle is then used to insert into the table or to search in it, it's then used in the same way, to speed up the comparisons.

For findIdx(), the non-leaf index type arguments behave differently than the leaf ones: up to and including the index of the target type, the search works as usual. But then at the next level the logic switches to the same as in beginIdx(), going for the first row handle of the first leaf sub-index. This lets you find the first row handle of the matching group under the target index type.

If you use $table->findIdx($itA, $rh), on Fig. 5 it will go through the root index to the index A. There it will try to find the matching position. If none is found, the search ends and returns a NULL row handle. If the position is found, the search progresses towards the first leaf sub-index type. Which is the index type B, and which conveniently sits in this case right under A. The position in the index A determines, which index of type B will be used for the next step. Suppose it's the second position, so the second index of type B is used. Since we're now past the target index A, the logic used is the same as for beginIdx(), and the first position in B2 is picked. Which then leads to the first row handle of the second sub-stack of handles.

|

| Fig. 5 FindIdx($itA, $rh) goes through A and then switches to the begin() logic. |

The method firstOfGroupIdx() allows to navigate within a group, to jump from some row somewhere in the group to the first one, and then from there iterate through the group. The example of manual aggregation made use of it.

The Fig. 6 shows the example of $table->firstOfGroupIdx($itB, $rh), where $rh is pointing to the third record in B2. What it needs to do is go back to B2, and then execute the begin() logic from there on. However, remember, the row handle does not have a pointer to the indexes in the path, it only has the iterators. So, to find B2, the method does not really back up from the original row. It has to start back from the root and follow the path to B2 using the iterators in $rh. Since it uses the ready iterators, this works fast and requires no row comparisons. Once B2 (an index of type B) is reached, it goes for the first row in there.

FirstOfGroupIdx() works on both leaf and non-leaf index type arguments in the same way: it backs up from the reference row to the index of that type and executes the begin() logic from there. Obviously, if you use it on a non-leaf index type, the begin()-like part will follow its first leaf index type.

|

| Fig. 6. FirstOfGroupIdx($itB, $rh) |

The method nextGroupIdx() jumps to the first row of the next group, according to the argument index type. To do that, it has to retrace one level higher than firstOfGroupIdx(). Fig. 7 shows that $table->nextGroupIdx($itB, $rh) that starts from the same row handle as Fig. 6, has to logically back up to the index A, go to the next iterator there, and then follow to the first row of B3.

As usual, in reality there is no backing up, just the path is retraced from the root using the iterators in the row handle. Once the parent of index type B is reached (which is the index of type A), the path follows not the iterator from the row handle but the next one (yes, copied from the row handle, increased, followed). This gives the index of type B that contains the next group. And from there the same begin()-like logic finds its first row.

Same as firstOfGroupIdx(), nextGroupIdx() may be used on both the leaf and non-leaf indexes, with the same logic.

|

| Fig. 7. NextGroupIdx($itB, $rh) |

It's kind of annoying that firstOfGroupIdx() and nextGroupIdx() take the index type inside the group while findIdx() uses takes the parent index type to act on the same group. But as you can see, each of them follows its own internal logic, and I'm not sure if they can be reconciled to be more consistent.

At the moment the only navigation is forward. There is no matching last(), prev() or lastGroupIdx() or prevGroupIdx(). They are in the plan, but so far they are the victims of corner-cutting.

No comments:

Post a Comment